Asef Bayat's Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring (2021) offers a unique perspective on the revolutions of the Arab Spring, moving away from traditional state-centric views. Instead, Bayat places ordinary people, the subaltern, and their daily practices at the center of revolutionary analysis. He argues that revolutions are not only political phenomena marked by regime changes but are also deeply embedded in everyday life, making his work a significant contribution to the study of revolutions. His focus on the grassroots, particularly marginalized youth, women, and the urban poor, presents a more comprehensive and distinct understanding of the revolutionary process.

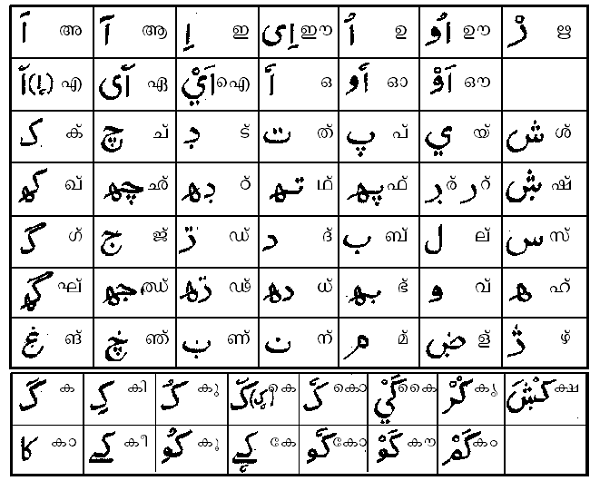

At the heart of Bayat’s analysis is the idea that everyday practices and nonmovements—dispersed but persistent actions of the marginalized—shape the trajectory of revolutions. The revolutions that began in Tunisia and Egypt in 2010-2011 were not merely top-down events orchestrated by political leaders but rather involved ordinary people engaging in acts of resistance and asserting their right to a dignified life.

He emphasizes that while macro-political changes might appear limited or even failures, such as Egypt's return to military rule, the real impact of the revolutions can be found in the lasting changes in social practices, attitudes, and subjectivities. He refers to these uprisings as “refolutions”—movements aimed at compelling regimes to reform rather than completely overthrowing them. This concept is central to understanding the 21st-century revolutions, which, unlike their previous exemplary counterparts, often lack charismatic leaders, a clear ideology, or radical structural changes.

Revolution, Everyday Life and the Subaltern

Perhaps one of the most significant contributions of this work is the concept of intertwining the extraordinary (revolution) with the mundane (everyday life). Bayat explores how the daily struggles of ordinary citizens can spark and shape revolutions. He writes that the story of revolution is not just what happens at the top but what transpires at the grassroots level. The mobilization of the subaltern—including street vendors, unemployed youth, and women—in Tunisia and Egypt was as crucial as the actions of political elites in Tahrir Square or the Constituent Assembly of Tunisia.

The author uses a wealth of data, personal anecdotes, and archival materials gathered from his extensive fieldwork to explore these dynamics. His nuanced approach brings depth to his analysis of how ordinary people were deeply involved in revolutionary activity long before the Arab Spring officially began, showing that their participation was not spontaneous but built on years of daily struggles.

The book delves into the experiences of the subaltern under both autocratic regimes and during the revolutions. In doing so, Bayat uncovers the nuanced and often overlooked actions of marginalized groups. The poor, plebeians, youth, women, and other social minorities engaged in revolutionary activities that often defied traditional notions of political movements.

For instance, women played a critical role in shaping the revolutionary landscape. Chapter 5, “Mothers, Daughters, and the Gender Paradox,” presents an in-depth look at how gender norms both limited and empowered women in the revolutionary context. It highlights the paradoxical nature of women’s participation, where they were both at the forefront of protests and yet faced limitations due to patriarchal social structures.

The youth, in particular, are portrayed as central actors in these uprisings. The demographic shift in Arab countries led to the rise of an educated yet economically marginalized youth population, many of whom participated in grassroots movements. Bayat notes that the expansion of higher education, coupled with the lack of corresponding economic opportunities, created what he calls the “middle-class poor”—a group instrumental in organizing and participating in these revolutions.

Concept of Nonmovements and a Critical Analysis

Bayat builds on his earlier work, Life as Politics, to introduce the concept of “nonmovements,” the collective actions of individuals who are not formally organized but whose practices nonetheless lead to significant social change. These nonmovements played a critical role in the Arab Spring, where the everyday struggles of millions of people coalesced into mass uprisings. Street vendors, slum dwellers, and informal workers all engaged in daily practices that challenged the status quo, pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in authoritarian states.

In Revolutionary Life, Bayat extends the idea of nonmovements to show how they helped maintain the momentum of the revolution even after the initial euphoria had faded. In Tunisia, for instance, the revolution continued to manifest itself in the persistence of protests and demands for social justice, despite the return of establishment figures to political power. In Egypt, on the other hand, the return to military rule under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi demonstrated the fragility of revolutionary gains when the energy of nonmovements dissipated or was suppressed.

Bayat’s emphasis on the everyday and the subaltern offers an essential corrective to state-centric and elite-focused analyses of revolutions. His work is a reminder that while political structures are essential, they are often shaped by forces outside of formal political institutions. His ethnographic approach allows for a more granular understanding of the social dynamics at play during the Arab Spring.

However, while Bayat’s approach is compelling, a critical reflection suggests that his focus on nonmovements and everyday life underplays the importance of formal political institutions in sustaining revolutionary change. For instance, in Tunisia, while grassroots movements played a crucial role in initiating the revolution, the eventual success of the revolution in transitioning to democracy was also due to the role of political elites, such as the national labor union UGTT, in negotiating compromises.

Additionally, Bayat's concept of “refolution” raises important questions about the limits of nonviolent revolutions in the face of entrenched state power. While peaceful protests and nonmovements can erode the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes, they often struggle to dismantle the institutional structures that underpin these regimes. This is particularly evident in Egypt, where the revolution ultimately led to the re-establishment of military rule.

To conclude, Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring is a vital contribution to the study of revolutions, offering a fresh perspective that centers on the experiences of ordinary people rather than political elites. Its emphasis on everyday practices, nonmovements, and the social side of revolution provides a more holistic understanding of the Arab Spring and its aftermath. Above all, Bayat’s work challenges traditional notions of revolutionary success and failure, suggesting that the real measure of a revolution’s impact lies not only in whether it leads to regime change but also in how it transforms everyday life and social relations. In this regard, Revolutionary Life is an essential read for anyone seeking to understand the complexities of the Arab Spring and the broader dynamics of revolutionary change in the 21st century.